Regulation of Community Water and Sanitation (Temporary or Permanent?)

Saturday, July 30, 2016

Unknown

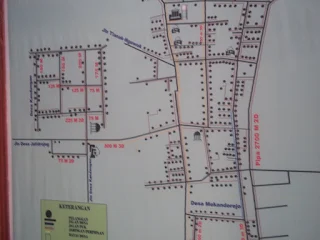

Picture: water network diagram in Tlanak

One of the most interesting findings in our research is the relationship between community based water services and existing water utilities. We find patterns of cooperation and conflict. One of the underlying reason is the different perception as to whether community based systems should be considered a "temporary" solution or a "permanent" solution. This still cannot be resolved among policymakers:

Our FGD revealed that there are unresolved fundamental differences among regulatory stakeholders, in terms of whether CB should be perceived as a temporary “approach” with the overall intention to integrate it to the PDAM or “institutional” system in the future or whether it stands equally to the existing “institutional” system.[152] This difference has created tensions and confusion in practice, but more importantly, brings negative impact to policy and regulatory reform.

According to a government official some PDAM consider that CB Watsan is a temporary solution in their business plan – thus Community watsan network is regarded as parts which can be co-opted and taken over, since PDAM considers that the only one who is entitled to provide services are PDAM and the rest can only provide services through concession with PDAM.[153]

In addition, community watsan projects may, to some extent, contravene the exclusive natural-legal-local monopoly granted to PDAM. Furthermore, there is indication that some successful community watsan intitiative have grown large in a way that could match or even surpass existing PDAM.[154] How these community watsan initiatives could coexist with existing PDAMs or – to maintain the economies of scale – be merged with or acquire existing PDAMs is a problem yet to be solved.

The importance of modeling behaviors and future development in order to develop understanding of the relationship between PDAM and CB was a common response across the FGD. Two fragment-scenarios may be a suitable approach to be able to foresee regulatory developments. The first is to view community watsan as a “temporary” entity which exist only for a certain period and can be “annexed” by PDAM for certain reason such as economic scale or environmental conditions such as surface water quality in which CB model would no longer be compatible and larger scale investment would be required for treatment. The temporary approach is consistent with existing regulation -- since existing laws considers that the only one who is entitled to provide services are State or Regional Owned Enterprises -- whilst the other may only provide services in concession with PDAM. If this scenario is to be taken, then regulatory reform should focus on short term solutions with the overall objective of integrating the whole system to PDAM.

The second scenario is to perceive CB as a completely different model that can develop, expand and supersede PDAM or other “institutional” system. CB is thus treated equally with “institution”. As, at present, there is no CB model above district [Kecamatan] level, this model would be quite speculative. In this model, the regulatory framework should acknowledge the diversity of models in services provision and allow either CB or institutional model to acquire each other. FGD participants challenge the conceptual distinction of CB/”institution” based on assets size, coverage or natural monopoly. Thus, in this scenario, the regulatory framework should be able to foresee the CB model transformed into large scale water utility.

Read the full research report.

Visit project page: Regulation of Community Water and Sanitation.

Recent Comments